For many centuries, theologians and philosophers have equated the idea of omnipotence with absolute control over all things, believing “that God’s power, omniscience, and providence would be unacceptably compromised if one did not affirm that all events in the universe, including human choices and actions, were foreordained and foreknown by God.” (Oxford Handbook of Free Will, 35)

So this leaves little room for the idea of free will. But is there any way that free will can work in harmony with the sovereignty of God? Does it have to be a choice between one or the other?

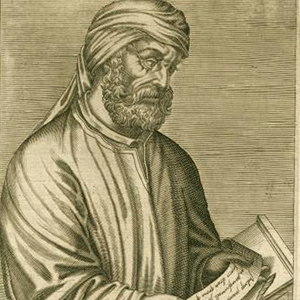

For Tertullian, omnipotence does not mean absolute control. Rather, God reveals that he is all-powerful when he justly responds to everything that men and women freely choose to do. When he shows himself merciful to the repentant, he reveals his power. When he shows himself stern with the sinner, he reveals his power. And thus, God’s all-powerfulness lies not in his choice to control humans, but in his ability to respond to them righteously in any and every situation. No matter what people do, God will show himself to be good and fair. In Against Marcion 2.13 he writes:

Thus God is wholly good, because in all things He is on the side of good. His omnipotence is ultimately revealed as He displays both his ability to save and to punish. . . I would question his ability to deal with humans if he were only able to do one, but not the other. And thus even the display of God’s justice reveals the fullness of the divinity himself, showing him as the perfect Father and the perfect Master: he is a father in his mercy, a Master in his discipline; a Father in kindly authority, a Master in his severity; a Father who is loved affectionately, a Master to be feared. He is loved because he loves mercy more than sacrifice, but he is feared because he hates sin. He is loved because he prefers a sinner's repentance rather than his death, but he is feared because he rejects those who don’t repent. (ANF 3, 308, updated)

Tertullian argued that no matter what people do, God always finds a way to show his goodness, beauty and his fairness. Things can shake him, but they can’t deter him:

He will be moved, but not subverted. He will respond accordingly in each circumstance. Every action provokes a feeling in him: anger in response to the wicked, and indignation in response to the ungrateful, and jealousy in response to the proud. . . . But he shows mercy when people lose their way, and he is patient even with the unrepentant . . . he does whatsoever is necessary to bring about the good. (ANF 3, 310)

Tertullian challenges us to re-think the idea of sovereignty. Is absolute control really the greatest display of God’s power? Is the ability to program humans to think, act and speak exactly as he wants them to really the ultimate demonstration of omnipotence? What if God’s sovereignty is displayed in his ability to respond to whatever people do by showing kindness, justice and righteousness?

In the next posts , we’ll look at how this framing of divine sovereignty shaped Tertullian’s understanding of prayer.

- Details

- Category: Series 1: The Efficacy of Prayer